by Chris Evans

“We were trekking through snow up to our waists and the wind was so intense that we could barely stand up. But none of us said we’re not filming here. The production wanted extreme winter conditions, so that’s what we delivered.”

These are the words of LM Matt Palmer/LMGI, talking about shooting an episode of HBO’s post-apocalyptic series The Last of Us in Waterton Park, Alberta.

Demand for shooting in extreme conditions is getting bigger, insist many location managers. This despite the rise of new technology, like virtual production, proving successful in simulating environments.

If anything, productions are looking to go further and pushing the extremes, partly thanks to the new technology, which has improved comms, navigation, heating and with drones getting to far-flung places.

But that doesn’t mean it’s gotten easier. Location managers still need to give serious thought to locations, factoring in things like costs, production expectations, logistics and, increasingly, dramatic changes in weather conditions.

Vatnajökull, Iceland. Photo by Elli Cassata/LMGI

Slower process

Elli Cassata/LMGI

But their first task is often explaining to producers and directors that everything takes more time. “They tend to underestimate and we have to explain that we are walking in at least a foot of snow, so everything is about 30% slower. It’s not appealing to them, but we say your five-day shoot is more like eight days,” says Elli Cassata/LMGI, owner and SLM at Pegasus Pictures in Iceland (who also covers Norway, Sweden and Greenland).

LM Ken Brooker/LMGI agrees. “If you’re used to shooting six to eight pages a day, you might be lucky to get four on the mountains if you’re smart and well prepared.”

It’s the same with prep. If it’s normally a week, stretch it to 10 days. And anticipate potential delays to shooting days due to the weather. “Snowstorms can suddenly come and you can’t see or move,” warns Cassata.

Doug Dresser/LMGI, Million Dollar Highway Ouray, CO

Handling expectations

It’s also important to manage the project’s creative vision.

“I had one producer who came to me with a storyboard and about 30 images of Iceland from the internet (some of which I’d taken myself) showing four different seasons in every corner of the country, incorporating the Northern Lights and midnight sun, saying they wanted all of it, but only had a four-day shoot,” laughs Jason Roberts, owner of PolarX, based in Svalbard, a Norwegian archipelago in the Arctic.

LM Stacy Kane/LMGI, co-owner of Kane House Films, adds: “We get producers just saying they want to shoot in Alaska, and I ask them where and what type. We have tundra, rainforests, Arctic conditions, etc. We take them around the region so they can get their head around it, factoring in the best place for getting equipment, infrastructure and matching the budget.”

Doug Dresser/LMGI

SLM Doug Dresser/LMGI says: “I just completed a movie in Colorado where the director wanted to film at a specific snowy mountain cabin during a snowstorm. But we had to travel on snowcats in four feet of snow, which then surrounded the cabin, and so we rejected it.”

Sometimes the country won’t work. For the TV series True Detective: Night Country, the story was based in Alaska, but the production team filmed in Iceland instead. “Temperatures can drop to -40 degrees in Alaska, which is not sustainable for filming,” says Jethro Ensor/LMGI, one of the SLMs on the series.

The fact that Alaska lost its financial incentive for filming has also been a huge factor. “We’re not getting as many big-studio features because of it, more indie projects and nature docs,” concedes Kane.

Photo by Ken Brooker/LMGI

Right time

Timing of productions is also important. Many arrive to scout a few months before the shoot when the landscape and conditions are completely different.

“I stood once on a fjord in the middle of August in heavy rain trying to explain that by winter, it will be frozen and white,” says Roberts.

“For True Detective: Night Country, there was no snow through prep up to Christmas. We then had a break and the day we left, Iceland had a huge snowdrop, which meant we could film in the new year. But the snow was up to our waists. It was the perfect setting for our crime scene, but difficult to operate in. We had to actually remove a level of the snow to prep everything, while making sure it still looked virgin. It was tough,” admits Ensor.

Not many know that in the Arctic summer, there’s not much snow and actually quite bare rock. “If they give a storyboard image and mood feeling, then I can tell them the season they’re after, and how to get the crew in. For instance, where the runway is for the plane and where they can stay, which might be on boats or ships,” says Roberts. “Sometimes they’ll be factoring in things like chauffeurs, stopping traffic and police fees to their budget, as if they’re filming in London. So I have to change their mindset to think about things like getting a ship in and the crew onboard efficiently because it’ll be your unit base.”

Ken Brooker/LMGI

Filming on the glaciers can also vary depending on the place. “In Iceland, for example, with the glaciers close to the coastline, it’s a steeper track up the mountains to the edge of the glacier, which can be tricky in wintertime. So we choose inland glaciers for that season,” says Thor Kjartansson/LMGI, a SLM with leading Scandinavia-based outfit Truenorth, that supported the Mission: Impossible shoots in Norway. “Some glaciers are flatter than others, or have more mountain rain and views of the ocean or lagoons. Then there’s varying elements like ice caves, glacier tongues and frozen glacier lagoons.

“For some of the projects we’ve worked on [including The Midnight Sky with George Clooney], we’ve had to split the glaciers into sections, meaning this part is accessible for main unit, this is for second unit and this is for a small VFX unit.

“On The Tomorrow War film, we also had to transport equipment to and from set in the dark (early morning and at night) because of the limited light in October/November during the day.”

Palmer insists the ideal is for scouting to take place a year before the shoot so the location should look similar, but few productions have that luxury of time.

Matt Palmer/LMGI, The Last of Us, Waterton National Park

Go local

Location managers also advise productions to rely on locals. “They know where to shoot, what’s needed and potential dangers,” says Cassata.

They can also help get permits, which can be straightforward in places like ski resorts, but trickier in other locations.

A good example is Antarctica. “You can jump up and down, but it’s gonna take you six months to a year to get the permits,” warns Palmer.

“On The Last of Us, we were filming at a national park with lots of federal restrictions,” explains Palmer. “We wanted a crew of 200 and they preferred a maximum of 30. So it required negotiating and help from high-level political people, but we eventually managed to get 300 in.”

“On The Last of Us, we were filming at a national park with lots of federal restrictions,” explains Palmer. “We wanted a crew of 200 and they preferred a maximum of 30. So it required negotiating and help from high-level political people, but we eventually managed to get 300 in.”

For productions that bring in their own crew, “We ensure they’ve had experience in snow and ice. We’ve seen American grips turn up in Iceland in shorts and T-shirts,” says Cassata.

“Equally, we had a Japanese crew come to the Nordic region in summer to shoot a commercial, and we told them like 10 times, they’ll just need a T-shirt and light jacket, but they turned up in Canadian goose jackets and snow goggles,” says Roberts.

Transport and logistics

Once plans and prep are in place, there’s the tough task of bringing crew and equipment in for the shoot.

Most productions base themselves in a place with infrastructure and equipment available that’s a short distance to the mountains or glaciers.

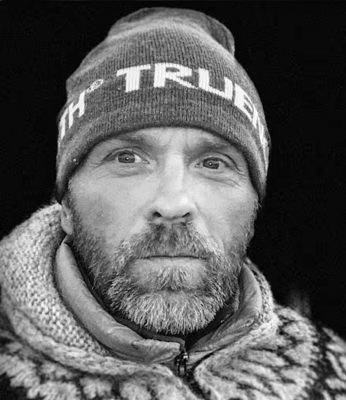

SLM Thor Kjartansson

“In Svalbard, you can stay at a nice hotel and then in no time be in the glaciers, highlands and mountains,” says Kjartansson.

It’s a similar story on Alberta, Canada’s Fortress Mountain. “You don’t need helicopters to get most gear in because there’s infrastructure there. You just have to factor in that it takes days to get equipment up and down in snowmobiles,” says Palmer.

Some productions like Mission: Impossible, have chosen to base themselves on ships. “But that takes planning time. Productions think they’ll just hire a ship like it’s off the shelf, but it’s hard and you have to know how many crew you’ll have,” says Roberts. “We did one shoot where we had to have three ships instead of the planned one because the numbers changed.”

Mandi Dillin/LMGI

For the more remote locations, there will be a big base camp with large orange hardware tents that trap heat. “We’ll set this up the night before, then fly everyone up in a helicopter so they have a warm space,” says SLM Mandi Dillin/LMGI.

“To get to remote locations, we’ll often use super jeeps, which are special utility vehicles that are built from two massive jeeps on 46-inch tyres. You need to cross-load your gear into those vehicles,” adds Cassata.

Kane says: “It’s about weighing up how remote you want to be. There are glaciers we can drive to or others that have landing spots for the helicopter. I can also tell you every mail plane, charter operator and planes with skis that can, land on glaciers up high in the summer.”

On Aquaman and the Lost Kingdom, Kjartansson and his team managed to get out to Greenland to do some splinter (second unit) work. “It’s like no other place in the world with these massive icebergs. The vastness in wintertime is unbelievable. We flew out, then took boats and used drones to get in between the icebergs.”

But actually basing a production in Greenland would be a lot harder in terms of logistics, access and costs. “You’re gonna put three zeros at the end of your budget at least,” says Palmer.

Getting to some of these locations can also be treacherous. Says Kjartansson, “We had to shuttle crew out from our bases in Reykjavik and Dalvik to the more remote locations for True Detective: Night Country and the winds were so strong that we saw coaches on their sides.”

Palmer insists though that “remote locations don’t necessarily have to be more difficult or expensive, they can be easier and cheaper with efficiency. The key is talking to locals and dealing with closed roads.”

Equipment

As for transporting the equipment, the large majority will be placed at the main camp/production base. Then for the more remote, challenging environments, it’s about packing light but sensibly. “The more stuff you have, the more things will get buried or freeze up,” warns Brooker.

“We tend to avoid big lamps on the glacier and never use a 12K because getting a generator up there is a nightmare,” explains Cassata. “We are limited with what we can take on the snowmobiles, but we can bring technocranes because they have the gators on the belts.”

It’s the same with camera equipment. “You use softer cases instead of metal ones and picking the right cameras is key,” says Cassata. “We had a fancy new one for a shoot with digital displays made of liquid crystal, but it froze. One of our operators managed to take it apart and convert it back to analogue,” says Brooker.

Matt Palmer/LMGI, The Last of Us, Waterton National Park

“Having new tech at our fingertips is great for checking weather, getting better shots, communicating with satellite phones, checking the internet and heating clothing, etc., but it can also be far more complicated and things go wrong,” adds Palmer.

There are some tricks of the trade, though, especially for protecting the equipment.

“Condensation on the glass can be a problem because productions go from the freezing cold to the hotel where it steams up and then go out again and it freezes. Instead, we tell them to leave the cameras and lenses in the truck outside overnight. Just plug it in and put a lens cap on. They often say, ‘What if it gets stolen?’ But who’s going to take it? A penguin?” laughs Cassata.

SLM Kane adds: “We bring a lot of extra, heated-up batteries and put hand warmers in seal skin mittens and hang them on the camera so the cameramen can operate and keep their hands warm.

“We also bring an extra camera in case one goes down. We can’t wait in a remote location for another one to come from LA.”

Then there’s all the other equipment to take, like sanitary facilities with chemicals to break things down, tents and catering (sometimes lunch is flown in), including the right type of food.

“It needs to be energy-rich in terms of nutrients because in that environment, you’re burning so many calories just wading through the snow,” says SLM Ken Brooker.

Mandi Dillon/LMGI, Django Unchained toilet sled

Crew support

Maintaining crew welfare is tough but vital. Shooting in the winter cold is extreme. There’s usually only a small window of sunlight. And yet productions can still turn up unprepared.

“I often have to talk to the HoDs about the crew they’re bringing. No one’s got time to babysit anybody up there. If they’re not willing to bend, then they’re going to be a liability,” says Brooker.

SLM Dillin adds: “Many of them have filmed around the world or been snowboarding (and bring that gear), but they can soon run into trouble. Not only is it -40, but they don’t realise that filming in the snow is actually like filming in the desert, in that it gets dry and dehydrated, all the moisture comes out of the air. They don’t want to drink water because it seems strange in the cold, but it’s vital.”

It’s the same with food. “We have to remind crew to keep doing everything they would normally. It’s boring but if they don’t, hyperthermia can set in,” adds Ensor. “They soon come around and many wear the insulated bibs we provide with shiny space-age metal inside to keep them warm.”

“On the film The Revenant, they even had a separate Heat Team whose sole job was to keep everyone warm,” says Dillin.

Ken Brooker/LMGI, Filming Santa’s Village at Whistler Olympic Park, BC, Canada for Noelle

Keeping safe

Safety is paramount. This is where local expertise and good prep again come into play. “We always scout for crevasses and cordon off a safe zone where everyone can walk,” says Cassata.

Ensor adds: “It’s about being disciplined. On regular sets, the team move around freely to look at different angles, but you can’t do that here. There are fissures and cracks everywhere. We always count people in and out each day.”

Brooker also points to the importance of mountain guides and health and safety experts to navigate the environment and everyone wearing the right gear. “This is something that no production should scrimp on.”

Kjartansson warns temperatures can vary from +10 to -20 pretty quickly, so you need proper gear, not only for the cold, but also rain and even sleet. “We send a list to our crew of clothing that’s needed and appropriate,” he says. “Then we have a store at base camp in case anything’s missing.”

Weather change

But it’s not just about managing the cold, the weather can dramatically change in many ways, from lightning storms to extreme blizzards, which has got worse with climate change. Expert guidance and latest weather apps certainly help. “A lot of productions will bring in a meteorologist as a consultant,” says Brooker.

But even when fully prepared, sometimes freak conditions can interfere with productions and they need to adapt quickly.

“On The Revenant, we’d chosen Calgary because you would expect it to have a lot of snow in wintertime, but there wasn’t,” says Dillin. “It was too warm to even make snow because it was a Chinook winter, when the warm wind blows in. And the snow had turned to mud. We had to bring truckloads of snow in.”

Elli Cassata/LMGI, Jokulsalon mid February

It was a similar story on The Last of Us. “We had planned to shoot in February because it was the best time for winter conditions, but about five weeks after the first scout, the snow where we wanted to film had gone and the lake that was frozen had melted. We had to shift in 400 truckloads of snow from other parts of the national park—they wouldn’t let us bring it in from outside for fear of contamination nor use fake snow—and had to get fans to create wind in a place that is normally one of the windiest in the province,” says Palmer.

“A producer of a forthcoming show recently asked me when the snow will be gone, but I had to say it’s hard to know. We could have little snow at Christmas, then get a three-foot dump in May.”

“On one shoot, we had to bail quickly because we saw a cloud coming. We had flown onto a glacier in lovely blue skies in summer, but sure enough, fog quickly came in,” says Kane. “We always have a safe out, like a pilot, on every location.”

But inevitably, sometimes crew can be stuck on a location. This is where contingency planning is key.

“I’m usually prepared to sleep about 35 people on the mountain if we get weathered in,” says Brooker. “We bring in sleeping bags, food supplies, required medication and shelters, things like that, which never get used, but just in case.”

Kane agrees, saying: “On Ruth Glacier, Alaska, we also know where all the cabins are, so there’s at least some shelter and food. I know a crew that was stuck there for 10 days once.”

Palmer adds: “We did a sunset shoot on a high ridge at Watertown where sudden strong winds meant the crew were stranded because the helicopter couldn’t get to them, while we had porta potties flying in the air and the lunch tent collapsed.”

The key is having a strong producer who knows how to get things done. “They need to have the mindset that ‘yes, it’s a really nasty day out, but we can make it work,’ that’s where the magic is,” insists Kane.

Weather aside, there are several more factors to consider, including protecting the set. “We found an untouched snowfield for one project, and the DoP and his team, for reasons I’ll never understand, just walked straight through it, even though it was tapered off,” says Palmer.

Fortunately, some of this can be fixed “with snowblowers and rakes and dressing stuff up,” says Brooker. “But it’s important to break the area up beforehand into sort of highways for stash, shooting, bathrooms, food and drink, etc., so everyone knows where to walk. I always put together a prep memo on the call sheet.”

Doug Dresser/LMGI, Kinik Glacier, Alaska

Cast

Meanwhile, handling the actors depends greatly on whether they embrace the experience. On Mission: Impossible – Dead Reckoning Part One, the cast and crew loved the experience of being on the ice and bonding on ships with no internet. Hayley Atwell even decided after wrapping one day to drive the dog team back to the main unit.

But you still have to carefully consider safety and logistics for the actors. “Getting trailers to the remote locations is hard. So, we have to put up tents with heaters and blankets and carpet on the floor,” says Cassata. “Between takes, some are just happy to sit in the front seat of the SUV with a heater on and then step out to do their scene.”

It can be a big challenge though. “They’ll be wearing big coats and then strip down to period costumes in -35 degrees and try and look fine,” says Palmer. “Bear in mind that exposed skin can freeze within about 20 seconds in those temperatures.”

Filming in these conditions for the cast and crew is really tough and exhausting, expending energy just walking around, constantly shovelling, making pathways, getting stuck, managing the wind and cold. But you can get the best footage and it’s a great experience.

“Productions can try and cheat mountain conditions on green screen or in virtual production studios, but it’s not the same as being there, flying helicopters in the Arctic or cast and crew sitting on a ship staring at the ice caps. It’s also easy to spot the fake from the real on screen,” insists Roberts.

“None of the 145 crew on the BBC drama series The North Water, which shot stunning exteriors on location in the Arctic, and interiors in a studio, is going to tell their grandchildren about being in the sound stages.”