The team from Iceland’s Truenorth leads the cast and crew

of HBO’s Emmy-winning True Detective: Night Country

into a magical and chilling landscape…

INTO THE DARKNESS:

SURVIVING TO TELL THE TALE

by Shaun O’Banion

All photos courtesy of HBO, except as noted

In the midst of the pandemic, HBO decided to pursue another season of their Emmy-winning anthology series True Detective. The resulting fourth installment—True Detective: Night Country—teams Emmy winner Jodie Foster as Officer Danvers and Kali Reis as Officer Navarro as they investigate the mysterious disappearance of eight men from an Arctic research station in the fictional mining town of Ennis, Alaska—a town so close to the Arctic circle that it exists in perpetual darkness for eight months each year. There the detectives must also confront the darkness they carry in themselves as they dig into the haunted truths that lie buried beneath the eternal ice.

With previous seasons featuring all-male leads and set in Louisiana, California and the Ozarks, respectively, the execs envisioned a fresh location and a new perspective with a female protagonist. They found the perfect storyteller in Mexican-born writer-diarector Issa López, who had been sketching out a plot for a “whodunnit” even before HBO approached her to join the series.

“Iceland is a magical place. We have an endless gallery of classical nature, with a variety of looks. The light is ever-changing, and the surreal drama of most locations here is astounding.”

—Truenorth LM Einar Sveinn Thordarson/LMGI

López had always been fascinated by mystery novels and stories of real-life unsolved murders. She recalled hearing of one particularly grisly tale as a child known as “The Dyatlov Pass Incident”: In 1959, an experienced group of scientists from the Soviet Union’s Ural Institute had set out on foot for a research expedition. They were later discovered not far from camp, with some grotesquely frozen to death from what appeared to be some gruesome physical trauma on the ice. What had happened during the night that caused these men to cut their way out of their tents and flee the campsite?

“The details don’t make sense and they died in the ice,” relates López for screendaily.com, “so, I thought, ‘murder mystery, ice, the unexplainable demise of a group of people.’

“Now all I needed was everything else. The story, characters and what happened to the men.”

López pitched a modern take on the Dyatlov Pass incident as the central mystery, resetting the series in Alaska and imbuing the narrative with flourishes of indigenous culture, environmental contamination and an unsolved murder.

Once the pilot was crafted, veteran producer Mari-Jo Winkler joined the project and she and López headed to Alaska to flesh out the details.

“We wanted to understand the culture of the Inupiaq indigenous communities and the physical place, shares Winkler. “We scouted in -22 degrees Fahrenheit, rode snowmobiles across the frozen ocean and visited different locations that were scripted to get a true sense of it all.”

Alaska can get down to -40 degrees in the coldest months,” adds production designer Dan Taylor, “which seemed like too much, not just for the crew, but for equipment as well.”

The scout confirmed that the high Arctic wouldn’t be suitable for shooting a large-scale, long-form series.

Patagonia, Newfoundland and Winnipeg were all considered as alternative settings, but it was the production company Truenorth that presented the most compelling case for Alaska to be played by Iceland.

Truenorth Iceland

Truenorth Iceland

When the team at Truenorth received word that HBO was looking for an environment that could double for Alaska, they sent a photo package to the producers. “It was immediately clear to the creative team that Iceland had a lot to offer beyond just being a visual match,” says Winkler.

It also helped that Winkler had been introduced to the principals at Truenorth back in 2014 when, after deciding to take a solo trip to Iceland, some of the folks at Truenorth had helped map out her journey.

Founded in 2003, LMGI business partner Truenorth has established itself as one of the leading production service companies in the industry, with offices in Iceland, Norway, Greenland, the Faroe Islands, Finland, Sweden, Greece and the Canary Islands.

More than just a service company, Truenorth Iceland actually develops and produces its own projects for film and television markets worldwide, but in terms of major U.S.- and EU-backed films like Clint Eastwood’s Flags of Our Fathers or Ridley Scott’s Prometheus, foreign productions had, for the most part, only come to Iceland for shorter shoots.

The possibility of hosting a major series for the full run was something the Truenorth team very much wanted to make happen—so much so that they lobbied the government and were granted an increase in the incentive program to a very generous 35% cash rebate.

A Magical Place

SLM Thor Kjartansson

Truenorth SLM Thor Kjartansson/LMGI and LM Einar Sveinn Thordarson/LMGI had dispatched scouts, including LM Robert Garcia, to search for fish factories, hospitals, homes, offices and a number of lakes which would be critical to double for Alaska’s frozen ocean. By the time López, Winkler and Taylor arrived in Reykjavík, Truenorth had gathered a wealth of location possibilities for them to consider.

“Iceland is a magical place,” says Einar. “We have an endless gallery of classical nature, with a variety of looks. The light is ever-changing, and the surreal drama of most locations here is astounding.”

“Thor and Einar’s presentation convinced us that we could absolutely pull off recreating Alaska in Iceland from a visual standpoint,” says Winkler.

Another key element of the fourth season is that it takes place almost entirely at night. Iceland, like Alaska, has very little daylight from December through February, which was exactly what the production needed. But even more than that, Thor and Einar had shown that the country also had the infrastructure and skilled crew that could support the production in very harsh conditions.

HBO signed off quickly and the creative team settled on the core locations found during those early scouts. UK SLM Jethro Ensor/LMGI, fresh off the new series 3 Body Problem, soon arrived in Iceland to work out contractual details and to help sew up the remaining locations for HBO.

“I was excited to go out there to support Thor, Einar and Robert as they were already setting things up,” says Jethro.

By the time he arrived, the schedule was already shifting.

“If you’ve been in television for a while, that’s pretty standard for TV drama, but it meant that we had to rethink certain locations the guys had found in different areas,” he says.

Arriving late in the game might have been tough on another show, but Ensor says he was welcomed by the Truenorth team, and they found themselves aligned very quickly.

“For me personally,” says Jethro, “it was about kind of knowing Dan’s eye as production designer, seeing the storm of the schedule change coming and then working out how best to make it all work creatively. But honestly, most of that is down to Thor, Einar and Robert.”

Einar is equally effusive about Jethro. “He was absolutely essential for us. There is a real difference between the Icelandic way of doing things and the English way and Jethro was the perfect bridge between those methods, in addition to his experience on large-scale shows and his eye for locations.”

Silver Sky Mine

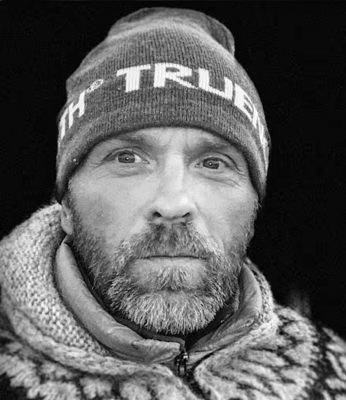

The Glacier Man

SLM Thor Kjartansson has been with Truenorth for more than 20 years, his background and skill set essential for working with production crews in extreme environments. The literal definition of the “outdoorsy type,” he began training with Iceland’s Air and Ground Rescue team at just 16 years old. Over the next three years, he would learn extreme survival skills and practice search and rescue (SAR) missions in a variety of situations.

“We specialize in searching for missing planes,” Thor says, “but we do it all: glacier rescue, people that have fallen into crevices or been buried under an avalanche, even just people who’ve gotten lost on snowmobiles in the wilderness or on the glaciers.”

While training with the team in his youth, he would never have imagined that his work or, frankly, his life’s passion would lead to a career in film and television, though it should be noted that he is still an active member of the rescue team.

Thor’s move into film and television came through a chance meeting on … where else? A glacier.

“I started operating Super Jeep and snowmobile expeditions,” he says, “and I would take people on excursions up in the Highlands and onto the glaciers.”

Thor quickly earned a reputation as a trusted and competent guide on the ice, and soon it wasn’t just tourists calling for his expertise.

“Over the course of about 10 or 15 years, I ended up supporting a lot of small TV crews that wanted to get up on the glaciers and I worked as a kind of fixer for them,” he says.

On one such trip in 2003, he met Truenorth founder and CEO Leifur Dagfinnsson. “It was just one of those moments where an opportunity comes up,” says Thor. “We were standing at the top of a glacier talking about the industry and he asked me if I would be willing to meet at his office. I did and I basically joined Truenorth a couple of months later.”

If you’re considering changing your career or considering anything, really, Thor highly recommends going to the top of a glacier to find clarity. “Yeah, I always say, ‘the best way to reach your thoughts is to go up on a glacier. You’ll find them up there,’” he laughs.

When Einar joined Truenorth three years ago, after having worked for 20 years in production services in Iceland and at the legendary Propaganda Films in L.A. before that, he recognized right away that Thor was a very unique individual, unlike anyone else he knew in the industry.

“Even on his days off, you won’t likely find Thor at home or even indoors,” he says. “He’s always somewhere out on the ice, in an ice cave or riding around on his snowmobile!”

Fiona’s House

Snow Chasers: Finding Ennis

With the series taking place entirely in a single Alaskan town, the team had to find a location that would work not only from a visual standpoint but would also get the right amount of snow and be able to work for a number of exteriors and interiors.

They ended up finding their Ennis in two different towns: The first was Dalvík, which is about five hours away from Reykjavík by car and only 45 minutes by plane.

Dalvík was selected early on due to the likelihood that it would get snow and, hopefully, hang onto it for a while—which it did—and distance aside, the town worked well and would end up being used for a number of key locations. But during scouting, the creative team had to imagine what everything would look like with snow … because there wasn’t any.

“We had zero snow all the way through prep up to almost Christmas,” says Ensor, “then we had the break and the day we left, Iceland had their biggest snowfall in a long time.”

Taylor remembers the exact day. “We flew out on the 16th of December and it was snowing heavily. Once we came back, the first issue was how we were all going to get back up to the town,” he laughs.

When they finally did, the snow was waist high!

“Perfect for the show,” says Ensor, “but very difficult to operate in. We had to remove a level of snow to prep, but still try to make sure it looked virgin. That was tough!”

Among the locations shot in Dalvík were the police station (an old post office), the liquor store (an old fisherman’s shed) and numerous exteriors such as the gas station and roads for a fair amount of driving scenes and an intense car-crash sequence.

“Dalvík was great because it didn’t matter if you looked to the west or the north, it basically had the same feel as a lot of the towns in Alaska,” says Thor, although he is quick to praise Dan Taylor and his art department.

“They had to bring in a lot of stuff to really sell it,” he says, “like American trucks, light poles, signage and things like that. Even for interiors. Things like American light switches and radiators which look different from ours. What they managed to do there was quite incredible.”

Despite being sold on the Dalvík locations, the creative team felt that they needed to expand the scale of “Ennis” beyond what Dalvik could offer.

“What we needed,” says Taylor, “was something with more of a commercial area. Dalvík, for me, made our exteriors feel too small, though I should note that the townspeople there were great about letting us take over things and it was a really fun location to work in.”

Checking the ice. Photo by Jethro Ensor/LMGI

To add that scale, they settled on Keflavik, a town in the Reykjanes region of southwest Iceland and about 45 minutes by car from Reykjavík. “Thor and Einar showed us a former U.S. Army base built by the Americans in the ’40s, and it was pretty great,” says Winkler.

There was only one problem … they needed to shoot in Keflavik first and preserve Dalvík for later in the schedule in the hopes of more snow. And there was very little snow in Keflavík.

“We needed to do our big exteriors there: the hotel, the mine, Hank’s place and Qavvik’s bar,” says Taylor, “so it had to be snow-covered.”

They ended up bringing snow down off the mountains.

“It was just truck after truck bringing in snow,” Taylor says, “and then we’d spread it around. The good news is that once we’d placed it, it would stay for a bit.”

Despite the difficulty, everyone agrees that the addition of Keflavík rounded out Ennis and added the scale they needed. Most of the high and wide exteriors were done there in addition to a few smaller yet pivotal sequences, such as Navarro’s run-in with a wayward polar bear.

“Don’t get me wrong,” Thor says, “there were a lot of locations on this show, but in a way, it was really like having only one big company move because we were able to find most of what we needed nearby Reykjavík in places like Fellsendi or Ölfus. So, it was kind of just shooting in the south and then our big move up to Dalvík in the north.”

The Ice Lake

There are a number of scenes in the show set on the frozen ocean and, while other shows might consider doing it all on stage somewhere with fake ice, comfortable water temperatures and a fair amount of blue screen, Night Country wasn’t your typical production. Thor and Einar believed they could safely shoot on real ice—though it took a bit of time to find a suitable location.

“We’d find a decent lake and then realize that it was near a main road so, once it got dark, you were going to have headlights all the time and noise which we obviously couldn’t have,” says Einar.

They ultimately settled on a location Thor knew well.

“There is a lake here on private property,” Thor says, “and I know the landowner personally. It’s actually a lake that I’ve been taking my kids to skate on for years.”

The owner was amenable, so the only questions were whether the conditions would work for the shoot once the lake froze over and if those conditions would hold in the weeks after. From a location perspective, it also worked for a number of reasons.

“The property is close to Reykjavík, which was going to function as our base, so that was obviously helpful,” Thor says, “and then what was great is that there’s only a single access road to the lake which meant that we could strictly control who went out there.”

Controlling who could access the lake was incredibly important in order to prevent distortion of the ice itself, as well as maintaining the integrity of the surface for safety.

“Being on the ice is exciting,” says Thor, “but it gets intense when you have to take 60 or 70 people—including your cast—and a bunch of equipment out there.”

With Truenorth, safety falls under the umbrella of the Location Department.

“It’s probably down to my background, but yes, we prefer to handle that aspect,” says Thor. “Safety is our number one concern.”

How Deep the Ice

How Deep the Ice

During prep, the first order of business was to go out in a boat and measure the depth of the entire lake. “There’s a big difference between falling through the ice if it’s 50 meters deep versus three,” says Thor, “and from the surface, you can’t tell how deep it is beneath the ice so, in the unlikely event that the ice gives way, we would be in the shallows.

“You have to think about it as if it could happen, so we chose areas where we knew that if something bad happened, anyone who went in could basically stand on their toes and we could pull them out.”

Initially, the weather gods smiled on the production, which Ensor jokingly credits to Thor, giving them an ideal situation for all the sequences they planned to shoot there.

“We got very cold weather right away,” Thor says. “It made the ice really clean so you could see through it and, at the surface, there were beautiful little cracks and air bubbles.”

If the lake had frozen in layers, with sleet or snowfall occurring between those layers, the ice would’ve appeared white which would have been fine but wouldn’t have looked as interesting.

“It was pristine,” Thor says with a satisfied smile.

“We ended up using that ice lake environment as a kind of one-stop shop for four or five locations,” says Taylor.

The ocean ice exteriors include where Navarro’s sister wanders out into the darkness, when Danvers falls through the ice (partially shot in a tank) and when Officer Prior disposes of evidence. They built sets on the edge of the lake as well, including Navarro’s house overlooking the sea.

One other pivotal sequence that was originally meant to shoot on the ice had to be moved: The “corpse-sicle,” as it came to be known.

At the start of the series, a literal pile of bodies is discovered out on the ice. It’s an even more gruesome version of what López had read about those Russian hikers as a child.

“It turned out that it just wasn’t practical to do that on the ice,” says Thor, “so we moved the scene to a field at another location and you can’t really tell it isn’t out on the ice.”

Basecamp. Photo by Einar Sveinn Thordarson/LMGI

Safety on the Ice

Knowing about his background in glacier rescue, the crew trusted Thor. If he said it was safe, it was safe. So, every day began with a briefing in which Thor and the team would cover protocols in case of an emergency and, for the entire lake shoot, safety divers in dry suits were on standby.

Once the lake had frozen over, they brought in an “ice engineer.”

“The engineer was with us the entire time we were there, and we were constantly taking samples and measuring the depth of the ice,” says Thor. “Those measurements help us calculate the weight strength.”

Once they determine it’s safe to work on, they also need to monitor who is going out on the ice to make sure that whoever does, comes back in.

Then they need to consider vehicles, equipment and their respective weight. Yes, that’s right, everything goes out on the ice—even the technocrane and a 4×4 truck that served as video village. There were even Arctic tents with heating!

“To do this, you have to very carefully consider the manner in which you distribute that weight,” says Thor. “For example, we had to bring a snowcat that pulls a kind of little shelter for cast, like a warming room. So, we’d bring that all the way out on the ice and we knew the weight of the shelter plus the snowcat. Then we’d do the math and determine that we needed to maintain 10 meters between the snowcat and the technocrane.”

There was one moment involving the technocrane, though, that gave some of the crew pause.

“We had been there shooting for a bit and we knew there was a layer on the surface and a little water underneath after about maybe 6 cm or 7 cm depth,” says Thor, “but we also knew that didn’t affect the strength of the ice. Still, the crew noticed the ice was starting to bend.”

A few of them came to Thor and voiced their concern.

“I totally respected them for making it known immediately,” he adds, “but we knew it was alright.”

After a chat, the crew members relaxed… Until they began to hear cracking sounds and what almost sounded like lasers or high-tension wires snapping.

“When it’s cold—and some of the nights were super cold even for Iceland—there’s tension in the ice,” Thor says.

The variation in temperature can range between -5 degrees Celsius up to as much as -20, and then there’s the water that’s flowing beneath the surface. These factors affect the tension in the ice, and it begins to make odd noises. Some of the sound can come from the surface, but most comes from below.

“It can sound like glass breaking or, other times, it’s this super weird sound, like, a whale or something. It comes from under the surface and, I mean, I totally understood these people. Like how in the hell should they trust my word alone, not having any experience working on the ice?” Thor says.

Thor and the team had to prove the solidity of the ice to the crew by drilling down, and with them watching, proving its depth. When Thor and the engineer took measurements, they found there was still 45 cm of ice beneath the thinner top layer.

“45 cm can hold the weight of a truck,” Thor explains.

The focus on safety extended off the ice, too, of course.

“When it comes to bad weather,” Thor says, “it doesn’t need to be up on a glacier or out on an ice lake. Our department would have to monitor the crew in the towns as well, because some nights a storm would come in and you’d have no visibility at all for maybe 10 minutes or more. Total whiteout.”

This meant the location team had to make sure everyone knew what to do in any extreme weather event and that the crew were accounted for throughout each day and at the end of the day, too, to make sure they’d gotten safely back to their hotels.

In the north, most of the crew were based in the town of Akureyri, which lies at the base of Eyjafjörður Fjord. It was about a 25-minute drive to Dalvík from there and so anytime anyone left, they’d have to caravan. And then there were the shuttle buses.

“Yeah,” Thor says. “Keeping the buses on the road was a thing, too. It didn’t matter that they were on the main street next to the town. You still had to look out for them.”

All in a night’s work for the man from Iceland’s Air and Ground Rescue and his team.

Photo courtesy of Jethro Ensor/LMGI

Surviving and Triumphant

True Detective: Night Country premiered on January 14 of this year to critical and commercial praise. It went on to receive six Primetime Emmy Award nominations, winning one for series lead Jodie Foster.

The series featured close to 60 practical locations over the course of its six episodes. For their work, Thor, Einar, Robert and Jethro received a nomination for “Outstanding Locations in a TV Serial Program, Anthology, MOW or Limited Series” at this year’s 11th Annual LMGI Awards.

Truenorth has capitalized on the awareness Night Country has given them globally and, as of this writing, the company has projects shooting in three countries simultaneously—a milestone.

“Night Country was a big jewel in our crown,” says Einar. “We proved that a project of that scale can be handled at the highest standard here in Iceland, and I’m proud, not only of what we accomplished on the show, but of this country.”

SLM JETHRO ENSOR/LMGI

When UK SLM Jethro Ensor/LMGI got the call from HBO to join the location team in Iceland on True Detective: Night Country, he didn’t hesitate to accept. “I was just there to support the Truenorth team as they were already setting things up. They’re world class!”

True Detective production designer Dan Taylor with SLM Jethro Ensor/LMGI. Photo courtesy of Jethro Ensor/LMGI.

Jethro had just finished up on the international Netflix series 3 Body Problem and already had a history with HBO as the SLM on the TV series The Nevers. His location cred would help the Icelandic team mesh with the English way of doing things.

He was raised with his sister between the small town of Pocklington in the north of England and the bustling city of London. Growing up, he hadn’t intended to get into the film and television industry, though film was a part of his life from an early age.

“We had one little cinema in our town,” Jethro recalls, “and you’d go with your family and the whole town would be there. I guess that’s where I first became aware of film.”

There was also a family friend who had access to the emerging video tape market. “We would watch stuff I definitely shouldn’t have been seeing at a young age like Jaws. And then, as I got older, of course, it was Alien. I loved John Carpenter. We were also raised on the Marx Brothers or the Jacques Tati film Monsieur Hulot’s Holiday. We really were exposed to quite a bit.”

By the time he attended university, Jethro thought he might pursue a career in the music industry. “I can’t play an instrument,” he says, “but I thought that was going to be the thing. Maybe get into being a roadie or a manager.”

But an opportunity to work as a floor runner on commercials changed everything. “When you’re a student, you go, ‘wait, someone’s going to pay me 50 quid cash a day to run around getting stuff, and they’ll feed me?! I’m in!’”

On one auspicious day, he was assigned to assist the location department. “That’s where this career began,” he says. “It’s like, ‘can you drop some letters off and, while you’re there, knock on a door for us?’ Well, I mean, yeah, of course I can go knock on a door and it’s actually fun because you never know what’s beyond it. Then you’re chatting with really fascinating people and it’s great.

“LM Keith Pettinato took me under his wing and started training me. It taught me that this is not just a job. You’re building a team and creating this camaraderie because you need that. I’ve carried that with me my whole career.”

After taking off for a couple of years to travel the world and even manage a bar in Sydney, Australia, for a bit, he returned to England. A call from his friend LM Rupert Bray pulled him back into the world of filmmaking. The two would end up working together for several years.

“Rupert really put me through it,” says Jethro. “You know, in those days, there were no Google maps or things like that. So, I’d have to make the movement orders and do all that stuff. And then I’d give them to Rupert, and he would mark them up or correct them with a big red pen on the recce buses.”

Eventually, he would move up to LM on an established UK series and TV movies which led to a career-making opportunity to work on The Hollow Crown, a massive production based on Shakespeare’s Richard III that entailed huge battle sequences.

“That was the first experience for me of the massive machine that is streaming television. It was a beast,” he says. “I think it worked out because I knew about crowds, I knew about period and I really knew how to find stuff. The one thing I didn’t really know then was the scale of VFX that happens on these shows. That was a huge learning curve.”

From then on, talking to the VFX team as often as possible has become his mission. “I’m very interested in the VFX guys because it’s helpful to have a sense of what they need because, you know, one day you turn around and suddenly there’s a 40-foot blue screen blocking a road that people had forgotten to mention,” he laughs.

All that learned experience carried him onto the HBO series The Nevers, for which he earned an LMGI Award nomination in 2021 for “Outstanding Locations in a Period Television Series.”

His newfound understanding of VFX definitely came into play on 3 Body Problem and in Iceland on Night Country, for which he would receive his second LMGI Award nomination, along with his Truenorth colleagues. This time in the category of “Outstanding Locations in a TV Serial Program, Anthology, MOW, or Limited Series.”

Having had great mentors of his own, Jethro believes in passing on what he’s learned. “I like the idea of ‘each one, teach one.’ There are always young people coming through and I try to impress upon my LMs and ALMs that they should really try to give everyone a chance. Despite the uncertainties in our industry, we want to build a generation of people that do this. And I’m really fortunate that I’ve got two people with me who’ve been with me for years. One is now a fantastic LM in his own right who I trust implicitly and it’s great to have that backing and that’s what you learn when you’ve got great mentors.”

(L-R): Robert Garcia, Anna Bjork Hilmarsdóttir, Einar Sveinn Thordarson/LMGI , Birkir Grétarsson Photo courtesy of Einar Sveinn Thordarson/LMGI

TRUE DETECTIVE: NIGHT COUNTRY LOCATION DEPARTMENT

Truenorth SLM – Þór ‘Thor’ Kjartansson/LMGI

SLM – Jethro Ensor/LMGI

Key LM – Robert Garcia

LM – Einar Sveinn Þórðarson/LMGI

LM (North) – Marino Sveinsson

ALM – Birkir Grétarsson

Location Coordinator – Anna Bjork Hilmarsdóttir

Key Location Assistant – Patrick Kristinsson

Key Location Assistant – Haukur “The Hawk” Henriksen

Location PA – Gabríel Marinósson

Location PA – Þórður ‘Dotty’ Kristján Ragnarsson

Location PA – Andri Enoksson