First Man Lifts Off

by Lisa R. Reisman

Photos courtesy of Universal Pictures and DreamWorks Pictures, except as noted.

Conspiracy theories be damned. It takes a village and then some to pull off getting a rocket to the moon, even a fake one. Based on the book of the same title by James R. Hansen, First Man is the story of Neil Armstrong, the first man to step foot on the moon. Location manager Kyle Hinshaw, LMGI took on the challenge of finding places that would make filming the event as authentic as possible on Earth. Director Damien Chazell’s (La La Land) vision for the film was that of a practical look, as if being filmed in real time. In a Los Angeles Times interview with Josh Rottenberg, Chazelle says, “I think it’s just that I have a particular aversion to very noticeable CG, especially for this subject matter.”

As First Man’s Location Office coordinator, I was able to get the inside scoop on First Man and it became the experience of a lifetime.

LISA REISMAN: Kyle, let’s introduce you to everyone. Tell me about how you got started and how long you’ve been in the industry.

Photo courtesy of Kyle Hinshaw

KYLE HINSHAW: I started my career in film school at Georgia State University. I worked on staff at Tomorrow Pictures during college, editing and producing small, client-based projects until I graduated. In 2009, I got an opportunity to work with a local location manager, Mike Riley, on a feature film for the Cartoon Network. He needed a location assistant who could make maps, and I jumped on that opportunity as quickly as I could. Luckily, I had some photoshop skills I picked up during my stay at Tomorrow Pictures, and was able to piece together some maps based on a few references he gave me. I continued to work my way up in the Location Department over the next few years, and ultimately started managing on 2nd Units and reshoots. I met a lot of really great producers that I stayed in touch with over the years, and one of those connections ultimately led to getting hired as the local location manager on Baby Driver and working with Doug Dresser, LMGI.

Photo: Kyle Hinshaw

LR: You and Doug Dresser won an LMGI Award for Best Contemporary Feature for Baby Driver. How did the challenges of First Man differ from putting together Baby Driver’s extensive and complex chase sequences?

KH: First Man was a very different type of project compared to Baby Driver. On Baby Driver, we were piecing together these incredibly complex driving sequences in urban areas with stunts and special car rigs, trying to figure out how we could accomplish the work in the daytime and scheduling around events in the city. Director Edgar Wright embraced Atlanta as the setting of the film, so we were shooting the streets as they really existed. Not much changed from a design perspective, even the geography of the chases were relatively true to the actual layout of streets in Atlanta.

For First Man, I was tasked with recreating NASA in the ’60s, and finding period-correct environments that production designer Nathan Crowley could make over and match to the iconic photos and footage on file with NASA. Some searches were easier than others—but most of the time we were finding locations that were originally period correct but had been updated. We would have to take them back in time a bit with set dressing, or hide their modern updates. The biggest challenge in Atlanta is the older architecture is slowly being demolished or updated, so we really had to dig deep to find everything. Nathan had these large bulletin boards in the art department where he posted reference photos and inspiration for each set we were creating. The script itself was so dense and contained so much jargon, I had to do a lot of my own research on what each building and piece of equipment was—so having access to those boards was really helpful for our scouts. We’d end up finding the locations by latching onto the key aspects of the set that we could recreate with a practical location—something that would catch the eye of the designer and get his creativity flowing. I’m happy to say that the only interiors that were built on stage were limited to the interior spacecraft. All of the other sets were achieved practically on location.

One interesting tidbit from the design aspect: NASA has been portrayed through very sterile and clean environments in other films and television. Damien and Nathan both wanted to show a different side—a grittier aesthetic that they found to be truer to life after researching all of the file photos and footage from NASA. So instead of looking for these massive, sterile environments, they encouraged me to look for grimy, raw spaces that Nathan would clean up a bit to counteract some of the mythology around this particular setting in American history.

LR: Any other project that would compare with the challenges of First Man?

KH: While each project holds its own challenges, I can’t think of another job that had some of these unique directives simply because we were matching a very specific milieu in our country’s history. Many times the script seemed somewhat insurmountable. The only way I know how to get my job done is break it down into smaller pieces and look at how it all fits. Nathan Crowley told me, “None of us have made a movie about NASA before. We’re all trying to figure it out.” First Man was unique because I was constantly having to source images for all of the scripted events. It was hard to imagine what was being described since I didn’t have a frame of reference for it. I found myself feeding these images to the scouts, trying to inspire them to think and look outside of the box. Sometimes that direction was a bit fluid because we didn’t know exactly what we were going to find. Nathan told me a few times, “I don’t know exactly what I’m looking for, but I’ll know it when I see it”—so a lot of times I was just trying to anticipate his needs and look for specific elements that matched the research photos … something that Nathan could build onto and turn into an exact match.

Sometimes this process was frustrating because the producers wanted to shoot in Georgia as much as possible to take advantage of the tax incentive. So I was asked to come up with seemingly impossible practical options for the launch pad and Swing Arm in Cape Canaveral (ultimately shot at a Georgia power plant in the middle of the state), a location that could double as Ellington Air Force Base in Texas (the Perry Fairgrounds), and the moon surface (the Vulcan Quarry in Stockbridge). We were not able to double the Vehicle Assembly Building in Cape Canaveral; we had to piece together a filming day with the actors in Cape Canaveral to accomplish those shots, but it was impressive to see how the locations we found in Georgia tied in relatively seamlessly with Cape Canaveral once the movie was cut together.

Ultimately for this film (and for most others), my process was to just dig in, break everything down to achievable goals and directions for the scouts, and keep looking until we either exhausted the search or found something great. Of course, once everything was found, I had to figure out how to communicate the shots and needs of the crew to the location owners so we could get the company in there and actually film. But finding it was half the battle.

LR: Discuss your role in the practical and authentic nature of Damien Chazelle’s vision.

KH: Initially, the producer and creatives were scratching their heads. Georgia is void of desert environments, so the initial thought was to create the lunar surface on the backlot at Tyler Perry Studios. Damien was not terribly excited about this prospect since the dirt here is red clay, and the site that we could use was only about 1-2 acres, surrounded by trees. It would have required green screen elements. The producers were concerned we would have some weather issues in January (we did). They wanted me to look into a large indoor space like the old Georgia Dome to turn into a super stage. However, there were a lot of practical challenges to creating that set. Bringing in all of the moon material would be very costly. Trucking in all the gravel and sand would have taken weeks and countless dollars to achieve the correct look, not to mention that there was no availability in those venues for the amount of time we would need. Damien was very insistent that the set had to exactly match the archival footage (down to the shadows the sun cast), particularly since the moon landing is one of the most well-documented events in history.

Photo: Kyle Hinshaw

Scouts Oshi Nightbird and Melanie Manning had great images of a quarry in Juliette, Georgia, that got the production designer really excited about the possibilities of building the moon in a practical location. The search quickly turned to a quarry where we could get a large amount of space that provided the scope of the moon. We landed at the Vulcan Quarry in Stockbridge. They had a large plot of land next to the quarry that used to be their old plant site. It had these enormous concrete pillars that they were planning to demolish, and the quarry manager agreed to getting that project completed in time for us to film. Damien was worried that there was too much working against us there to create the space that he needed. However, I took all of production’s concerns to Vulcan, and they assured me and the design team that we were in the best spot to achieve the looks we needed. They had massive machines on site that could sculpt the existing lot into whatever topography we needed using existing material. Any additional aggregate could be delivered within hours. The price was right, so we decided to move forward with this plan.

Nathan worked with his set designer to create a blueprint of the landscape that matched geographically to the Apollo 8 landing zone. I took this plan to the Vulcan Quarry, and worked with them on determining how to achieve this look with the aggregate and machinery on site. Vulcan demolished the remaining structures at our set and used their earth movers to grade and flatten about six acres of land. Then they dug a huge crater in the middle of the set, and created a 12’ berm around the perimeter of the set, establishing a matte line for visual effects. This berm also hid the base of the crane that the lighting department used. The DP had an experimental fixture fabricated for the shoot that burned at 200,000 watts to simulate the sun.

Nathan worked with his set designer to create a blueprint of the landscape that matched geographically to the Apollo 8 landing zone. I took this plan to the Vulcan Quarry, and worked with them on determining how to achieve this look with the aggregate and machinery on site. Vulcan demolished the remaining structures at our set and used their earth movers to grade and flatten about six acres of land. Then they dug a huge crater in the middle of the set, and created a 12’ berm around the perimeter of the set, establishing a matte line for visual effects. This berm also hid the base of the crane that the lighting department used. The DP had an experimental fixture fabricated for the shoot that burned at 200,000 watts to simulate the sun.

Once the set had been graded and the berm was in place, the quarry delivered multiple 100-ton loads of aggregate that were dressed into the set to match the powdery grey dust on the moon’s surface. If we had not found that particular site, the moon surface may have been much less impressive. We simply could not have afforded to build a set that size on a backlot, or in some arena or stage. None of these options would have allowed Damien the look he wanted without massive visual effects.

LR: Tell me more about the launch pad location at Cape Canaveral.

LR: Tell me more about the launch pad location at Cape Canaveral.

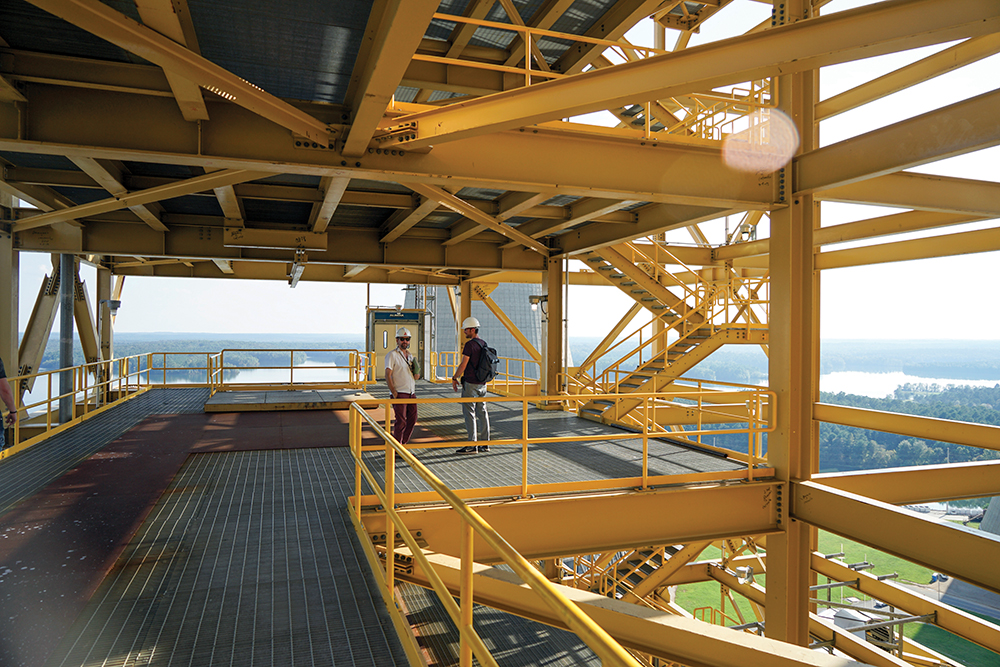

KH: The launch pad was difficult to find on location in the Metro Atlanta area. After looking at many research photos, we were able to determine that we needed massive steel structures that could convey the immense scope of the Vehicle Assembly Building and launch pads at Cape Canaveral. It was not going to be financially possible to film multiple days at the NASA facility, so we had to find a way to double everything. We worked very close with Mike Staples, the film representative at Georgia Power who got us in to scout numerous facilities. Plant Scherer in Juliette’s proximity to a large body of water helped sell the location as Cape Canaveral, along with the massive steel structures and working elevators attached to the coal plant.

There were three missions being launched from Plant Scherer, the Gemini and two Apollo, which made for some creative repurposing of what the power plant had to offer.

We staged a scene at the base of their SCR structure doubling the base of the launch pad, and built the upper gantry way and command capsule of the Apollo 8 on the roof to stage the scene where the astronauts walk out of the elevator and load into the rocket. The height of a Saturn 5 rocket is approximately the same elevation as Plant Scherer’s roof. This put the horizon in the perfect location for the camera. Also, beautiful Lake Juliette stood in as a perfect replacement for Lake Solana at Cape Canaveral.

The power plant was tough logistically because getting equipment to the top of the power plant was not easy—it took our construction department about three days just to load in. The plant itself had a lot of security protocols and safety precautions, so our location team had to go through training to learn their procedures and we developed a system to get the prep, shooting, and strike crews in and out of the facility as efficiently as possible.

Photo: Kyle Hinshaw

LR: What were the challenges to getting the locations signed, secured and prepped?

KH: Georgia Power took a lot of hand-holding. They had never opened up an active plant to a project of this size, and Plant Scherer is vital to their operations in Central Georgia. On top of security concerns, their facility houses massive amounts of coal and hazardous materials. Serious security and safety protocols have to be maintained. Georgia Power was committed to keeping us and their employees safe, so we had to be very detailed on our filming requests, and get all set plans pre-approved before we got the contract completed. It took multiple meetings, on-site visits and set plan proposals before everything was finalized.

There were three separate times that exterior filming had to be shifted due to snow. There’s not much you can do when there’s snow and ice in Georgia. The moon had already been dressed and sculpted by the greens department, so we just had to wait a day until it all melted.

Photo: Kyle Hinshaw

LR: Can you address the safety requirements and training at both the quarry and power plant?

KH: The quarry’s safety requirements of wearing a hard hat and steel-toed shoes were minimal in comparison to the power plant. We had to distribute personal protective gear to the crew—hard hats, ear plugs and safety vests. Our location team of about 20 people had to learn the different sirens for the plant—usually these initiated an evacuation protocol depending on what emergency situation was under way (fire, hazmat spill, dangerous weather, etc.). In the event of an emergency, we were responsible for evacuating the crew and performing a roll call at the muster station.

LR: Is there anything else you would like to mention about First Man?

KH: I think that there was a really cool integration of our practical LLTV crash location in Perry, Georgia, with the stage work. VFX took plate shots and projected them into the LED screen to create a virtual location. This was done multiple times in the interior spacecraft sets as well. The technology allowed us to seamlessly cut between the location and the stage.

All the hard work paid off. Variety’s Owen Gleiberman says, “The fact that space travel, viewed from the inside, could look and feel so much more abrasive and hazardous than we might ever have thought is part of the raw power of First Man.” When you get right down to it, the film was built on a solid marriage of locations, physical machines and creative SPFX to put together the filmed-in-real-time effect Chazelle was aiming for.

From my personal perspective, being a part of this project was an experience I won’t forget. It was distinct pleasure to watch all of this happen in well-orchestrated fashion between the director, production designer and the Location Department. With Kyle’s solid team in place, he knew just what each person could bring to the table, and it paid off in a credible film telling a wonderful story. Yes, it is possible to fake a moon landing—you really need just the right talent.